Pioneer Courthouse, Portland

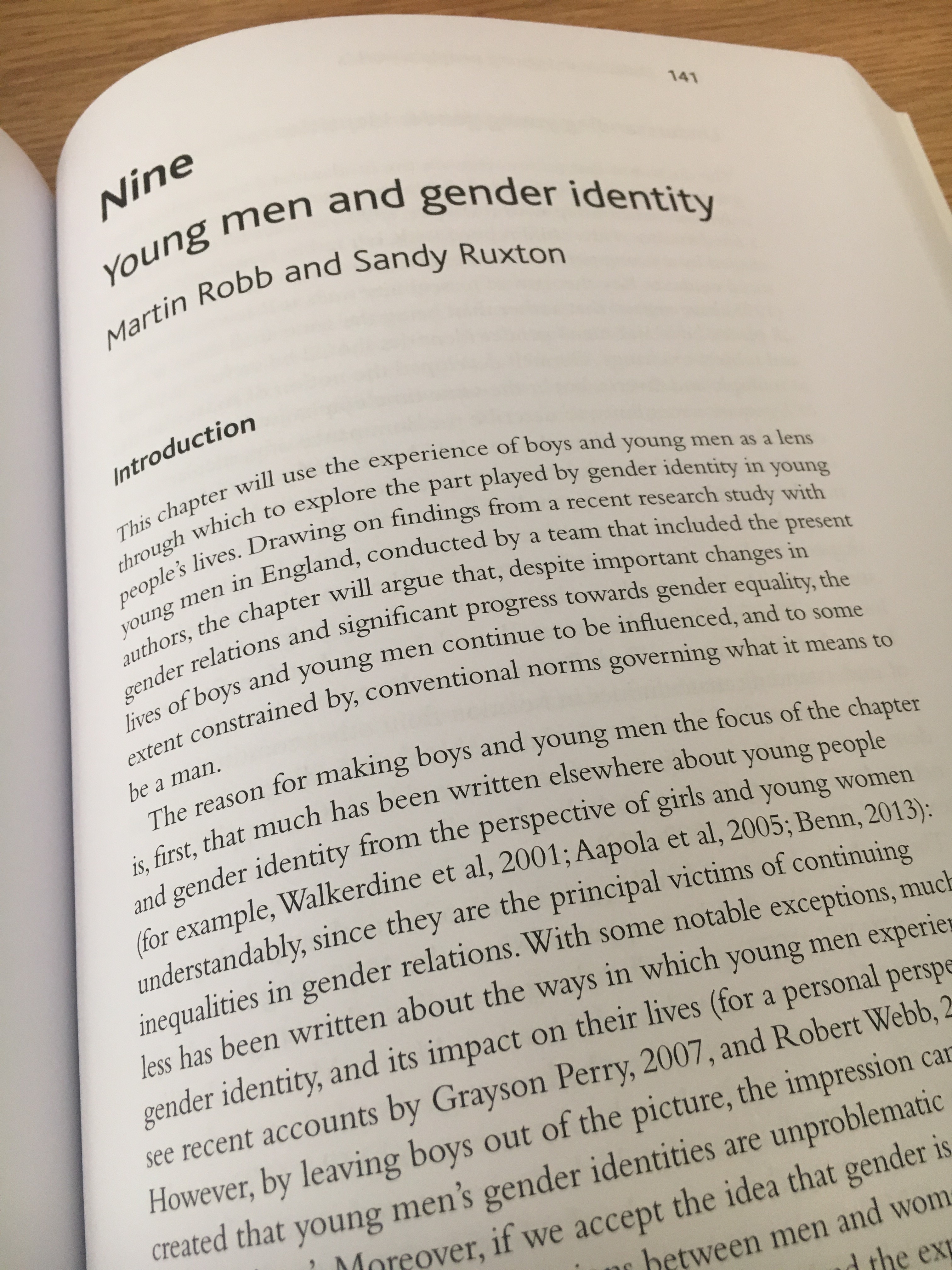

Last week I was in Portland, Oregon, in the United States, for a conference on ‘Care Ethics and Precarity’, organised by the Care Ethics Research Consortium. I’m a relative newcomer to care ethics: my interest in the field has grown out of my academic work on issues of gender, identity and care, and in particular my research on men’s care for children, whether as fathers or paid workers. The relatively new discipline (or, more accurately, interdisciplinary field) of care ethics, and feminist care ethics in particular, has helped me to think about the ways in which men develop a capacity to care, and has converged with my growing interest in phenomenology, a philosophical tradition that underpins the work of many care ethicists.

My own contribution to the conference was a paper on marginalised young men and the development of caring masculinities, which drew on two recent research studies in which I’ve been involved, and discussed the ways in which the family relationships of young men from disadvantaged backgrounds influence their capacity to care, attempting to frame this within the relational perspective on identity advanced by care ethics. (To download the slides from my talk click on this link: CERC2018presentation_MartinRobb2) It was a pleasure to find myself on a panel with Jeanne Enders and Lukas Robuck from Portland State University, and to discover surprising affinities in their work on the role of family relationships in the development of leaders in business ethics.

Presenting on ‘Young men, social disadvantage and the development of caring masculinities’, alongside Jeanne Enders and Lukas Robuck

The conference as a whole was an intellectually stimulating and challenging experience. It was a privilege to hear presentations by some of the key figures in the field, including Joan Tronto and Eva Feder Kittay, two of the ‘founding mothers’ of feminist care ethics. And it was good to finally meet people whose work I’ve admired from a distance – such as Carlo Leget from the University of Humanistic Studies in the Netherlands, arguably the ‘nerve centre’ of care ethics, Petr Urban from the Czech Academy of Sciences, with whom I’d previously been in email contact, and Maurice Hamington from Portland State University, whose writing on men’s embodied care I’ve found particularly inspiring.

Maurice also deserves credit for hosting such a well-organised and welcoming conference, in which careful attention was paid not only to scheduling a diverse programme of lectures, panels and presentations, but also to offering an aesthetically and socially pleasing experience, which included art, photography, music – and superb catering!

Carlo Leget and Maurice Hamington opening the conference

One of the things I really liked about the conference programme was the way it combined the philosophical and theoretical with the empirical and practical, with sessions ranging from explorations of ancient Greek understandings of care and precarity, through to a very moving presentation on work with prisoners, which included first-hand accounts – and poetry – by young men who had themselves been incarcerated (and whose powerful poem ‘Toxic Masculinity’ echoed many of the themes of my own presentation). Before attending the conference, my understanding of the concept of precarity had been fairly vague, but I came away with many new insights: Carlo Leget’s talk helped me to see that precarity could be chosen, as in the case of St Francis of Assisi, while Luigina Mortari drew out the etymological roots of the term, and Eva Feder Kittay’s keynote lecture clarified the difference between precarity and precariousness, in the process radically challenging the ways we understand the lives of disabled people.

Stephen Fowler and Noah Schultz give poetic voice to their experience of the American prison system

The conference also added considerably to my already extensive care ethics and philosophy reading list. To mention just a few: Carlo’s talk prompted me to want to re-read Simone Weil, Merel Visse’s presentation on abandonment aroused my interest in the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, and Petr pointed me towards political ethnographer Didier Fassin as a resource for understanding the (un)caring practices of the state.

Care ethics and politics: a few thoughts

A number of the conference talks had a political dimension, with a common theme being care ethics as an alternative or challenge to the current wave of neopopulism sweeping both American and European politics. I admit that I had some reservations about the ways the issue was framed, particularly in an important presentation by Joan Tronto, whose book Caring Democracy has been influential in this debate. From a British perspective, I have to confess that it was a little annoying to see Brexit listed, alongside the election of Trump and of reactionary governments in Europe, as an instance of right-wing populism, and I think it pointed to a possible weakness, or absence, in the anti-neopopulist argument as it was formulated by some speakers at the conference.

Joan Tronto

Firstly, the inclusion of Brexit in this list overlooks the large numbers of British people who supported the ‘Leave’ campaign from a left-wing position, or for reasons that were far from reactionary, such as dissatisfaction with a perceived democratic deficit in the European Union and concern about the growth of a bureaucratic European superstate and the concomitant erosion of national identities. Secondly, it points to a need not simply to dismiss so-called neopopulist movements as inherently wicked, but to try to understand the genuine feelings of dissatisfaction and alienation that give rise to them: in Italian political theorist Antonio Gramsci’s formulation, to identify the kernel of good sense within the common sense of neopopulism.

Both in her conference talk and in Caring Democracy, Tronto proposed care ethics as a framework for the renewal of democratic politics, in opposition to the undemocratic and authoritarian tendencies of neopopulist movements. But what if neopopulism itself is, at least in part, an expression of a desire for greater democracy and local control, in reaction to what are perceived to be distant and faceless supernational bureaucracies? In the words of British political commentator Paul Embery, it’s possible to view neopopulist movements as ‘defensive crusades against rapid cultural and demographic change, against the rapacious and disruptive power of global finance, and the weakening of democracy and sovereignty at the hands of remote and unaccountable institutions’.

What’s more, Tronto characterised neopopulism as a reaction to neoliberalism, whereas it could equally well be seen a rejection of paternalist state welfarism. There’s a danger that a care ethical approach could be perceived simply as a return to what political theorist Adrian Pabst calls ‘state-administered equality’, rather than offering a genuine alternative to the failures of both welfarism and neoliberalism. Incidentally, the British experience is a reminder that neopopulism is not only a feature of the political right: here in the UK we are currently witnessing a left-wing version that shares many of the features of its right-wing mirror image, including a cult of personality, media-blaming, conspiracy theories, and a strain of racism – in this case antisemitism.

If care ethics is to offer a real challenge to neopopulism, then surely it needs to understand the genuine feelings of alienation that have given rise to it, including the perceived loss of the communal and national identities that give meaning to many people’s lives: in Pabst’s words ‘a respect for settled ways of life, a sense of place and belonging, a desire for home and rootedness, the continuity of relationships at work and in one’s neighbourhood’. In other words, neopopulism could itself be seen as the expression of a desire for a renewal of relationships of care and connection, albeit often in a distorted form. Perhaps a care ethical alternative to neopopulism might incorporate some of the ideas developed in an alternative strain of British progressivism – the movement that has come to be known as ‘blue Labour’ – including work by thinkers such as Pabst, Maurice Glasman and Jonathan Rutherford.

Given its feminist provenance, it’s not surprising that care ethics tends to be associated with the political Left. But if it’s to offer a real alternative to neopopulism, and one that connects with the experiences and aspirations of ordinary people rather than imposing solutions from on high, then I would suggest that care ethics needs to avoid being tied too closely to one side of the political divide, and to offer a genuine challenge to the orthodoxies of both left and right.